Magallana gigas (Thunberg, 1793)Common name(s): Japanese oyster, Pacific oyster, Giant Pacific oyster, Miyagi oyster, Portuguese oyster, Pacific cupped oyster, Immigrant oyster, Giant oyster, Giant cupped oyster |

|

| Synonyms: Crassostrea gigantea, C. gigas, C. laperousii, C. posjetica,C. talienwhanensis, Dioeciostrea hispaniola, Lopha posjetica, Ostrea chemnitzii var. elongata, O. cymbaeformis, O. gigas, O. gravitesta, O. laperousii, O. posjetica, O. rostralis, O. talienwhanensis |  |

| Phylum Mollusca

Class Bivalvia Subclass Pteriomorpha Order Ostreoida Suborder Ostreina Family Ostreidae |

|

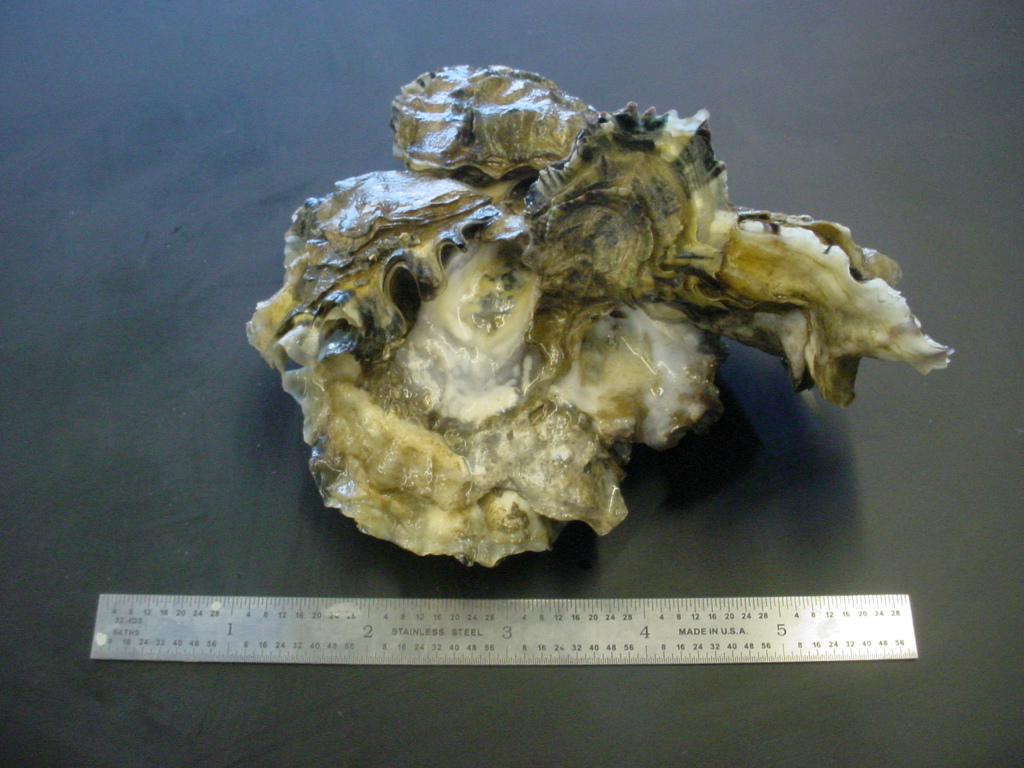

| Magallana gigas group from Padilla Bay. One large individual is on the bottom, and at least 4 smaller individuals are attached to its top (right) valve. Scale is inches. | |

| (Photo by: Dave Cowles, July 2005) | |

How to Distinguish from Similar Species: This is the largest local oyster; and usually the most commonly encountered one. The other local oyster, the native Ostrea lurida, is much smaller, does not have the conspicuous frills on the valves, and grows to no larger than 8 cm in height (often much less).

Geographical Range: Widely introduced on the west coast (and worldwide). Prince William Sound, AK to Newport Bay, CA. Scattered in many bays where oyster culture has taken place. Very common in Willapa Bay on the SW Washington coast, and in Departure Bay and the Georgia Strait in British Columbia.

Depth Range: Intertidal to 6m

Habitat: Firm sediment or rocky beaches

Biology/Natural History: The shape of this oyster is quite variable. The species was introduced from Japan in the early 1900's (to Washington and British Columbia in 1922) and is the most important aquacultured species on the US West Coast. The japanese littleneck clam Tapes japonica and the Japanese oyster drill Ceratostoma inornatum, as well as the intestinal parasitic copepod Mytilicola orientalis were apparently introduced to our coast along with this species. May live 20 years or more. Often contains irregular, non-lustrous pearls. Predators include predatory oyster drill snails, the crabs Cancer magister, Cancer productus, Cancer oregonensis, Hemigrapsus nudus, and H. oregonensis, some sea stars, and the black oystercatcher (bird). The blue mud shrimp Upogebia pugettensis is a problem on commercial beds of this oyster because it digs sediment from its burrows and smothers the oysters with sediment. The oyster typically attaches to hard substrates, such as rocks or the shells of other oysters. The oysters are imported as very small individuals (spat) and raised in commercial oyster beds. They are said to poorly reproduce in California, so are found only in the oyster beds. I have seen many oysters in apparently natural conditions here in Washington, so they must be able to reproduce at least a bit better here. Sexes are separate in this species, but an individual may change sexes (especially in the winter) and may alternate being male and female. Natural populations in Japan tend to favor protandry, and the largest individuals are likely to be females, especially if they are alone instead of in an aggregation (Yasuoka and Yusa, 2016). A few are simultaneous hermaphrodites (both male and female at the same time). Spawning occurs from May to October (Suquet et al., 2016). They outgrow native oysters, probably partly because they are more efficient filter feeders, and can feed on nannoplankton, which native oysters cannot do. Occasionally they are influenced by a red tide (usually by the dinoflagellate Gonyaulax catanella) and become toxic to eat. Warm temperatures of 25 C or greater and salinities well over 39 ppt increase their production of heat shock proteins. 37 C is sublethal and 44 C is lethal (Yang et al., 2016).

Larvae of this species are very sensitive to increases

in

dissolved

carbon dioxide in the water (Barton

et al., 2012). Lower seawater pH triggers smaller size and

reduction

in survival in the larvae, but increased temperature of the seawater

partly

mitigates this effect. However, this mitigation is

accompanied with

increased production of enzymes used to detoxify reactive oxygen

species,

suggesting that the larvae are still under increased metabolic stress

when

at lowered pH and increased temperature (Harney

et al., 2016).

Exposure to polystyrene microplastics seems to decrease reproductive potential in the species (Sussarellu et al., 2016).

| Return to: | |||

| Main Page | Alphabetic Index | Systematic Index | Glossary |

References:

Dichotomous Keys:Flora and Fairbanks, 1966

Kozloff 1987, 1996

Smith and Carlton, 1975

General References:

Brusca

and Brusca, 1978

Harbo,

1997

Harbo,

1999

McConnaughey

and McConnaughey, 1985

Morris,

1966

Morris

et al., 1980

Niesen,

1997

Ricketts

et al., 1985

Sept,

1999

Scientific

Articles:

Barton,

Alan, Burke Hales, George G. Waldbusser, Chris Langdon, and Richard A.

Feely, 2012. The Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea

gigas, shows negative correlation to naturally elevated

carbon dioxide

levels: Implications for near-term ocean acidification

effects. Limnology

and Oceanography 57:3 pp 698-710

Charifi, Mohcine, Mohamedou Sow, Pierre Ciret, Soumaya Benomar, and Jean-Charles Massabau, 2017. The sense of hearing in the Pacific oyster, Magallana gigas. PLOS one 12(10): e0185353. https://doi.ort/10.1371/journal.pone.0185353

Harney, Ewan, Sebastien Artigaud, Pierrick Le Souchu, Philippe Miner, Charlotte Corporeau, Hafida Essid, Vianney Pichereau, and Flavia L.D. Nunes, 2016. Non-additive effects of ocean acidification in combination with warming on the larval proteome of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Journal of Proteomics 135: pp 151-161

Ruesink, Jennifer L., B.E. Feist, C.J. Harvey, J.S. Hong, A.C. Trimble, and L.M. Wisehart, 2006. Changes in productivity associated with four introduced species: ecosystem transformation of a 'pristine' estuary. Marine Ecology Progress Series 311: pp 203-215. doi 10.3354/meps311203

Salvi, D. and P. Mariottini, 2016. Molecular taxonomy in 2D: a novel ITS2 rRNA sequence-structure approach guides the description of the oysters' subfamily Sacconstreinae and the genus Magallana (Bivalvia: Ostreidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 179:2 pp 263-276. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12455

Suquet, Mark; Florent Malo, Isabelle Queau, Dominique Ratiskol, Claudie Quere, Jacqueline Le Grand, and Christian Fauvel, 2016. Seasonal variation of sperm quality in Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea gigas). Aquaculture 464: pp 638-641

Sussarellu, Rossana, Marc Suquet, Yoann Thomas, Christophe Lambert, Caroline Fabioux, Marie Eve Julie Pernet, Nelly Le Goic, Virgile Quillien, Christian Mingant, Yanouk Epelboin, Charlotte Corporeau, Julien Guyomarch, Johan Robbens, Ika Paul-Pont, Philippe Soudant, and Arnaud Huvet, 2016. Oyster reproduction is affected by exposure to polystyrene microplastics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113:9 pp. 2430-2435. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1519019113

Yang, C.-Y.; M.T. Sierp, C.A. Abbott, Li Yan, and J.G. Qin, 2016. Responses to thermal and salinity stress in wild and farmed Pacific Oysters Crassostrea gigas. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A-Molecular & Integrative Physiology 201: pp 22-29

Yasuoka, Noriko and Yoichi Yusa, 2016. Effects of size and gregariousness on individual sex in a natural population of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Journal of Molluscan Studies 82: pp 485-491

General Notes and Observations: Locations, abundances, unusual behaviors:

These two individuals were raised in a local oyster farm (Taylor

Shellfish Farms). This view

is of the right valves.

A few barnacles are attached to the valves.

This ventral

view shows the fluting

which is common on the ventral

end of the shell. Some of the edges of the mantle

of the living oyster can still be seen inside.

In this ventral

view the valve

has

been opened further and the animal tissue removed. The brown hinge

on the far (dorsal)

side can be clearly seen.

In this lateral view, the dorsal

end (hinge)

is to

the left and ventral

to the right. The right (flat) valve

is on top and the left (cupped) valve

is below. The animal tissue has been removed.

In this view the valves

have been fully opened. The valve

on the left is the left (cupped) valve

which is normally attached to a substrate. The valve

on the right is the right (flat) valve.

The broken hinge

ligament can be seen on the right valve.

The large purple stain inside the shell is the attachment of the single

large adductor

muscle. Note that the valve

height (vertical dimension in this photo) is greater than the

length

(lateral dimension in this photo), and that there are no winglike

extensions

near the hinge

as

are seen in scallops.

The shell height (horizontal dimension in this photo) can sometimes be very much greater than the length (vertical dimenstion in this photo), as seen in this dead individual found at Fidalgo Bay August, 2025. Photo by Dave Cowles

These

oysters can be very abundant, and when overgrown with barnacles can be

hard to even recognize as oysters. Nearly every large object in this

photo taken on a beach in Fidalgo Bay is an oyster. Photo by Dave

Cowles, August 2025

Authors and Editors of Page:

Dave Cowles (2005): Created original page