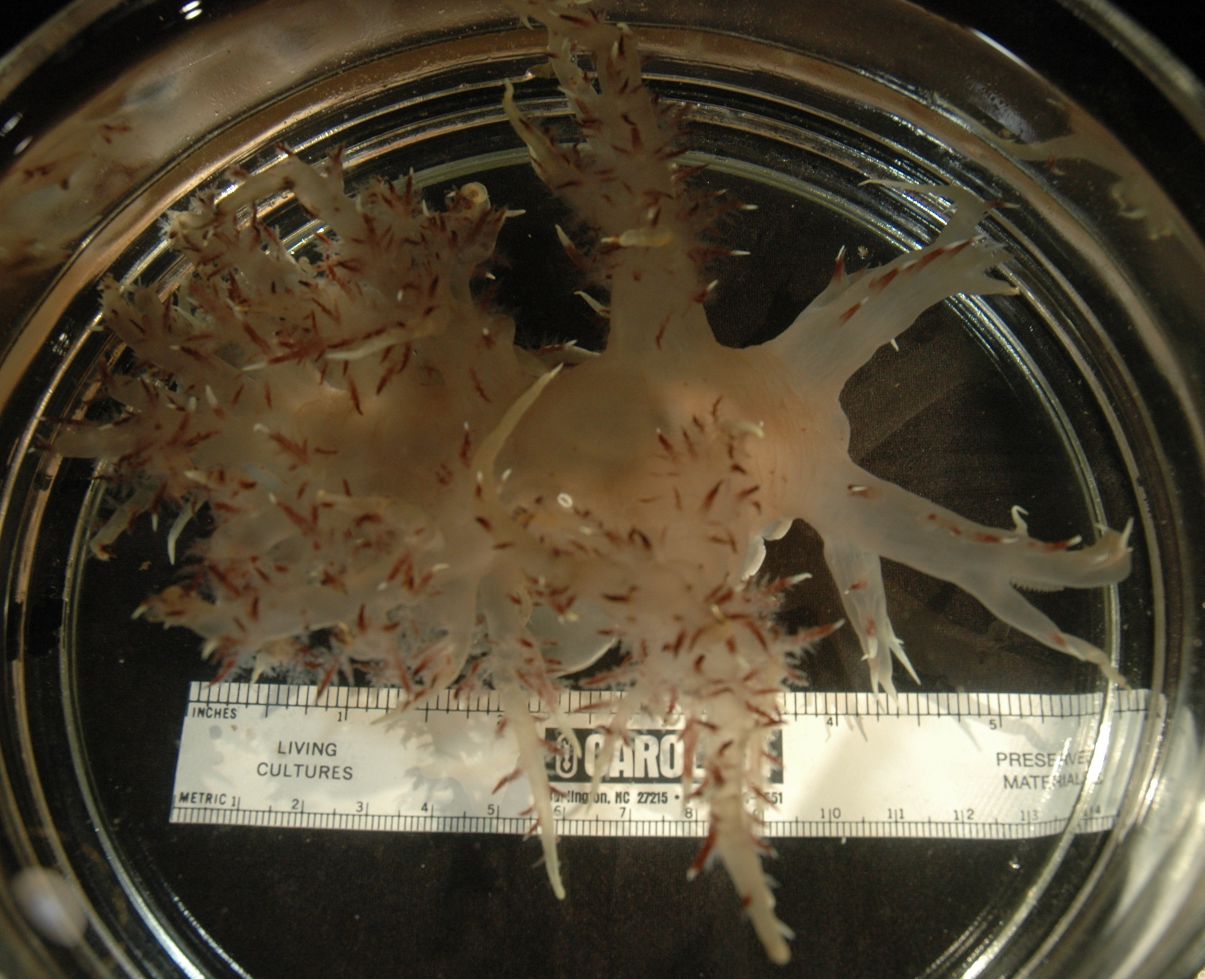

Dendronotus iris (Cooper, 1863)Common name(s): Giant dendronotus |

|

| Synonyms: Dendronotus giganteus |  |

| Phylum Mollusca

Class Gastropoda Subclass Opisthobranchia Order Nudibranchia Suborder Dendronotacea Family Dendronotidae |

|

| Dendronotus iris captured at 15 m depth, Coffin Rocks | |

| (Photo by: Dave Cowles, August 2005) | |

How to Distinguish from Similar Species: D. albopunctatus has a large, wide oral veil and yellowish white spots. Other Dendronotus, such as D. diversicolor, have no row of bushy projections along the posterior border of the rhinophore stalk.

Geographical Range: Unalaska Island, Aleutian Islands to Los Coronados Island, Baja California.

Depth Range: Mostly subtidal, down to 200 m. Sometimes seen on the surface over deep water, or in eelgrass flats.

Habitat: Mostly benthic on soft bottoms.

Biology/Natural History: This species feeds on the tubedwelling anemone Pachycerianthus fimbriatus, and on Nemertean worms. Besides its radula, it has large jaws for clipping tentacles off the anemone, and leaves the anemone looking as if it has had a bad haircut. The nudibranchs are sometimes pulled into the tube when the anemone retracts, but do not seem to be harmed by this. Predators include Pycnopodia helianthoides. This nudibranch is very active (see movie) and can readily swim by gyrating the body. Eggs are laid in white strings (photo), often on the tubes of their prey. The heart of this individual was large, and the heartbeat was easily seen through the dorsal surface (see movie).

According to Baltzley

et al., (2011), many gastropods, including this species, have

a special

network of pedal ganglia

in their foot which assists in crawling. The two main neurons

involved

produce pedal peptides which elicit an increase in the rate of beating

of cilia on the foot, resulting in crawling.

| Return to: | |||

| Main Page | Alphabetic Index | Systematic Index | Glossary |

References:

Dichotomous Keys:Flora and Fairbanks, 1966 (as D. giganteus)

Kozloff 1987, 1996

Smith and Carlton, 1975

General References:

Behrens,

1991

Harbo,

1999

Johnson

and Snook, 1955 (as D. giganteus)

Wrobel

and Mills, 1998

Scientific

Articles:

Baltzley,

Michael J., Allison Serman, Shaun D. Cain, and Kenneth J. Lohmann, 2011.

Conservation of a Tritonia

pedal peptides network in gastropods. Invertebrate Biology

130: 4

pp. 313-324

Web sites:

General Notes and Observations: Locations, abundances, unusual behaviors:

The white-ringed gonopore

on the right side, and the anal papilla

(light colored, to the right of the gonopore

and benind and below the right rhinophore)

can be seen in this photo.

Photo by Dave Cowles, August 2005

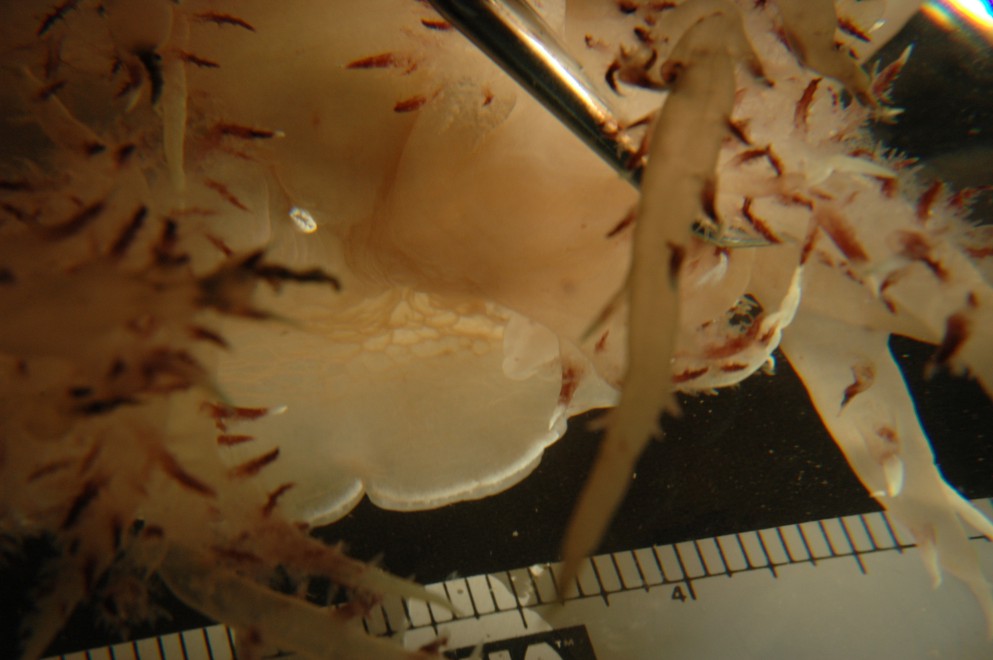

The rhinophores

(left one shown here) have a series of projections on the posterior

side.

The clavus

is

perfoliate, retractable, and projects from an anterior shelf.

It

has a crownlike ring of projections around it.

Photo by Dave Cowles, August 2005

The eggs are laid in gelatinous white strands, which are often attached

to the tubes of their anemone prey.

This nudibranch is very active, rapidly swirling its cerata

around when it crawls or swims. Click here

for a movie of the animal waving its cerata.

The heart of this nudibranch is large and easily seen beating through

the dorsal surface. Click here

for a movie of the heartbeat.

This individual was seen in a high intertidal tide pool

at Urchin Rocks,

July 2020 (Dave Cowles). Several people reported seeing stranded

individuals

of this species in the Salish Sea at about that period. Strandings may

occur after reproductive aggregations.

Authors and Editors of Page:

Dave Cowles (2005): Created original page