Penitella penita (Conrad, 1837)Common name(s): Common piddock, Flat-top piddock, Flat-tipped piddock, Piddock clam, Rock clam |

|

| Synonyms: Pholadidea penita |  |

| Phylum Mollusca

Class Bivalvia Subclass Heterodonta Order Myoida Suborder Pholadina Family Pholadidae |

|

| A Penitella penita shell from Toleak Point, WA. No animal is present. The right valve is shown. Anterior is to the right. The siphonoplax plates flare on the left. The protoplax covers the top right of the shell. | |

| (Photo by: Dave Cowles, Sept. 2006 | |

How to Distinguish from Similar Species: Penitella turnerae has no flaring siphonoplax. Penitella richardsoni is more irregular in outline. Zirfaea pilsbryi has spinelike teeth on the shell.

Geographical Range: Prince William Sound, Alaska to Baja California, Mexico

Depth Range: Mid intertidal to 22 m

Habitat: Usually boring into shale, almost entirely on the open coast (photo). Can bore into concrete.

Biology/Natural History: This is the most common species of piddock clam here in the Northwest. The shape and length of the shell varies with the hardness of the rock it is boring into. It is a significant agent in the erosion of coastal shale. The clams bore 4-5 mm/year, depending on the hardness of the rock, and may burrow to depths of 15 cm. Drilling seems to be entirely mechanical. The ridges on the shell seem to be produced between bouts of rapid drilling. Up to 22 ridges per year may be laid down. The animal grows as it digs deeper, so the deep portions of the hole are of greater diameter than the surface portions and the animal cannot back out of the hole. Since many clams may bore into the same rock, the clams often become crowded. The clams seem to be able to sense when their boring is approaching the burrow of another clam. When they approach another burrow they turn, often leaving only a millimiter or so of rock between the burrows. If the rock becomes so crowded that there is nowhere to turn the clam stops growing and remains stunted and sexually immature. The empty holes of piddock clams may contain small porcelain crabs, the flatworm Notoplana inquieta, as well as other crabs, worms, and sipunculids. Predators include the leafy hornmouth Ceratostoma foliatum. Sexual maturity is reached when the animal stops drilling and a callum covers the anterior gape in the shell. In soft shale the animal may mature in 3 years, while in harder rock it may not mature until 20 years or later. Mature animals may live for many years unless the rock is broken away. They can live for months in rock that has been buried by sand. In Oregon, spawning occurs in July.

| Return to: | |||

| Main Page | Alphabetic Index | Systematic Index | Glossary |

References:

Dichotomous Keys:Flora and Fairbanks, 1966

Kozloff 1987, 1996

Smith and Carlton, 1975

General References:

Carefoot,

1977

Harbo,

1997

Johnson

and Snook, 1955 (As Pholadidea penita)

Kozloff,

1993

McConaughey

and McConnaughey, 1985

Morris,

1966

Morris

et al, 1980

Niesen,

1994

Niesen,

1997

O'Clair

and O'Clair, 1998

Ricketts

et al., 1985

Sept,

1999

Scientific Articles:

Web sites:

General Notes and Observations: Locations, abundances, unusual behaviors:

Piddock clams are usually found embedded in their burrows in rock,

as is this individual. Photo by Dave Cowles

This view of broken shale at Shi Shi beach shows the holes many Penitella penita

(piddocks) have bored into it, plus the empty valves of one individual

which died inside the rock. Note how the anterior end of the piddock is

at the large, inner end of the hole, in drilling position, while the

siphons extend toward the opening. This piddock is 5 cm long. Photo by

Dave Cowles, June 2023.

This

view shows the piddock above after opening it. The structure projecting

from the hing area is the myophore, to which muscles attach.Length = 5

cm. Photo by Dave Cowles

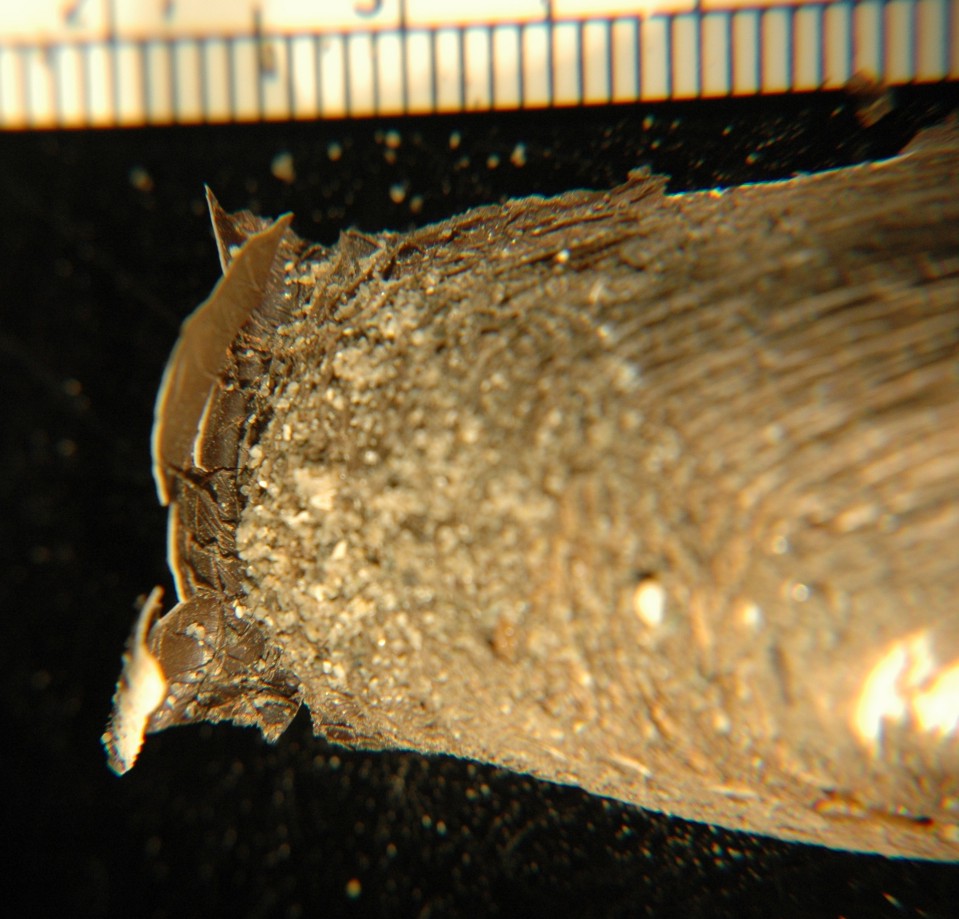

The

anterior, boring end of the piddock clam (to the right) is sculptured

dramatically differently from the posterior end (left), from which it

is separated by a modest groove. Photo by Dave Cowles

Although

the two valves of this dead individual have now separated, in this view

of the anterior, grinding end one can see that the gape between the

valves at the anterior end of this mature individual had been

sealed by a calcareous callum. The thick, shieldlike plate at the

anterodorsal end (to the left in this photo) is called a

protoplax. Photo by Dave Cowles

A view of the inside of the left valve. Note the projecting myophore

near the hinge. There are no hinge teeth. The siphonoplax,

which would normally be attached to the posterior end of the shell at

the

left, is detached from this specimen.

The chitinous siphonoplax

flares out from the posterior end.

The flaring siphonoplax

(on the posterior end, at the left; the mesoplax,

and the protoplax

(right) can be clearly seen in this dorsal view.

This posterior view clearly shows the flaring siphonoplax.

This ventral view shows that the anterior gape of the shell (to the

right) has been nearly completely sealed by the callum.

|

|

|

|

| Piddocks can be very abundant and can cause substantial erosion to coastal rocks. These piddock-infested rocks are at Shi Shi Beach on the Washington open coast. The sphonoplax of several piddocks can be seen in the lower photo. Photos July 2008 by Dave Cowles. | |

Authors and Editors of Page:

Dave Cowles (2006): Created original page