Chlorostoma funebralis (A. Adams, 1855)Common name(s) Black turban snail, black tegula, black top shell |

|

| Synonyms: Tegula funebralis |  |

| Phylum Mollusca

Class Gastropoda Subclass Prosobranchia Order Archaegastropoda Suborder Trochina Family Trochidae |

|

| Chlorostoma funebralis in the intertidal at Cape Flattery. Diameter approximately 2 cm | |

| (Photo by: Dave Cowles July 2004) | |

How to Distinguish from Similar Species: Promartynia pulligo has an open umbilicus. Chlorostoma brunnea has only one node on the columella. Both these species are brown rather than black.

Geographical Range: Vancouver Island to Baja California

Depth Range: Mostly intertidal

Habitat: Rocky intertidal of the outer coast. Rarely found in inland waters such as Puget Sound or the Straits of Juan de Fuca.

Biology/Natural History: This species is an algal grazer, on microscopic films, attached algae, and wrack. It prefers soft algae such as Macrosystis, Nereocystis, and Mastocarpus. It can be very abundant and conspicuous on the open coast (picture), especially in the mid-intertidal zone. The slipper shell Crepidula adunca settles preferentially on this species. The symbiotic limpet Collisella asmi (small, black) is often found on the shell as well (it grazes on the microalgae on the shell) but this limpet regularly "switches" Tegula hosts while the filter-feeding slipper shell stays put. The species is found more abundantly in open rocky areas than in areas heavily covered with algae. The animal crawls via retrograde (front to back) locomotory waves passing asynchronously down the two sides of the foot. They normally crawl about 0.6 to 0.8 mm/second but can nearly double this speed if they contact Pisaster ochraceous. They are said to be negatively phototactic. They excrete uric acid which probably helps in water conservation during low tide. Sexes are separate. Males tend to have paler soles of their foot than females have. Larvae grow rapidly but large individuals grow very slowly. Their shell produces prominent growth lines yearly. Large individuals may be 20-30 years old. Eaten by sea otters, red rock crab (Cancer antennarius), Pisaster ochraceous, some octopus in southern California, and some predaceous snails. It flees from Pisaster but not non-predatory seastars, and may escape predatory snails by climbing up on top of their shell. If on a sloping surface it simply detaches and rolls down the slope. One can observe this readily in the intertidal when approaching rocks with this species on them. Many roll down the rocks, but a large portion of these are hermit crabs inhabiting the shell. These snails were used extensively as food by California Indians. Their empty shells are a favorite of hermit crabs.

In an experimental test (Tepler et al., 2011), this species chose temperatures far below their physiological optimum temperature. This response may be due to the adaptive value of seeking refuge in cool, shaded places but likely precludes the species from functioning the most efficiently.

At least some members of this species have ripe gonads throughout the year in Oregon and California. In California they appear to spawn multiple times a year but only once in Oregon (late summer or fall). The most exposed sites are dominated by mature individuals while juveniles are more common in protected sites. Lifespan is 5-8 years in the southern part of the range but up to 30 years farther north. Egg production also seems to be greater in populations farther north, and larger individuals are more common there.

| Return to: | |||

| Main Page | Alphabetic Index | Systematic Index | Glossary |

References:

Dichotomous Keys:

Kozloff

1987, 1996

Flora and Fairbanks, 1966

General References:

Kozloff,

1993

Morris

et al., 1980

Niesen,

1994

Scientific Articles:

Cooper, Erin Elaine, 2010. Population biology and reproductive ecology of Chlorostoma (Tegula) funebralis, an intertidal gastropod. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oregon. 99 pp.

Darby, R. L., 1964. On growth and longevity in Tegula funebralis.

Veliger 6S: pp 5-7

Doering, P. H. and D. W. Phillips 1983. Maintenance of the

shore-level size gradient in the marine snail Tegula funebralis

(A. Adams): Importance of behavioral responses to light and sea star

predators. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 67: pp

159-173

Fawcett, M.H., 1984. Local and latitudinal

variation in predation on an herbivorous marine snail.

Ecology

65:4 1214-1230

Frank, P. W., 1975. Latitudinal variation in the

life history features of the black turban snail Tegula funebralis

(Prosobranchia: Trochidae). Marine Biology 31:181-192

Guzmán

del Próo, SA, T. Reynoso-Granados, P. Monsalvo-Spencer, and E.

Serviere- Zaragoza, 2006. Larval and early juvenile development in Tegula funebralis

(Adams, 1855) (Gastropoda: Trochidae) in Baja California Sur, México.

Veliger 48:2 pp 116-120

Moran, A. L., 1997. Spawning and larval development of the

black turban snail Tegula funebralis

(Prosobranchia: Trochidae). Marine Biology 128: pp 107-114

Paine, R. T., 1969. The Pisaster-Tegula interaction:

Prey patches, predator food preference, and intertidal

community structure. Ecology 50: pp 950-961

Paine, R. T., 1971. Energy flow in a natural population of

the herbivorous gastropod Tegula

funebralis. Limnology and Oceanography 16: pp 86-98

Tepler,

Sarah, Katharine Mach, and Mark Denny, 2011.

Preference versus performance: Body temperature of the

intertidal snail Chlorostoma

funebralis. Biological Bulletin 220: pp 107-117

Wright, R.C., 1975. Variations in size structure along a

latitudinal cline, growth rate and respiration in the snail Tegula funebralis.

MS thesis, San Diego State University

General Notes and Observations: Locations, abundances, unusual behaviors, etc.:

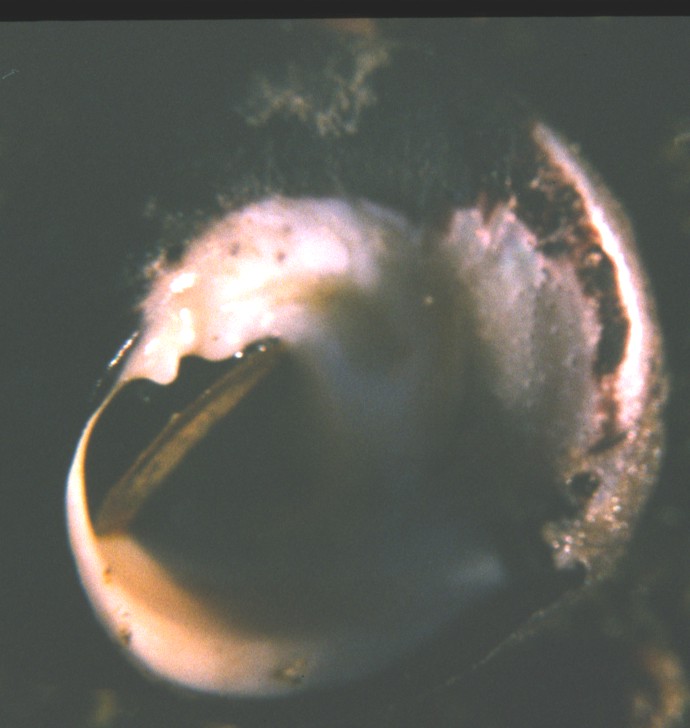

This view of the underside of C. funebralis shows the operculum, the closed umbilicus (brown stain), and the two

nodes on the columella (bumps just above the operculum)

Chlorostoma funebralis are often found aggregated at low tide, as in this photo taken at Shi shi beach, August 2005. Photo by Dave Cowles

Here is another aggregation in a tidepool, on red algae.

Photo

by Dave Cowles, August 2005

Note also the eroded spire, which is common on this species.

Most Chlorostoma funebralis have a bare shell with

an eroded

spire. Some, however, such as this specimen in a tidepool at

Little

Corona del Mar, CA, may be completely covered

with a short, thick coat of bushy red algae. Note also the

black

foot of the living snail. Photo by Dave Cowles March 2005

This aggregation is in the intertidal at Point of Arches, south of

Shi Shi Beach.

Chlorostoma funebralis crawls along the sandy bottom

of a tidepool

near Rialto Beach, WA at low tide, leaving a trail behind it.

Authors and Editors of Page:

Dave Cowles (2004): Created original page