Dendraster excentricus (Eschscholtz, 1831)Common name(s): Pacific sand dollar, Common sand dollar, Sand dollar, Eccentric sand dollar |

|

| Synonyms: Echinarachnius excentricus |  |

| Phylum Echinodermata

Class Echinoidea Subclass Euechinoidea Order Clypeasteroida Suborder Scutellina Family Dendrasteridae |

|

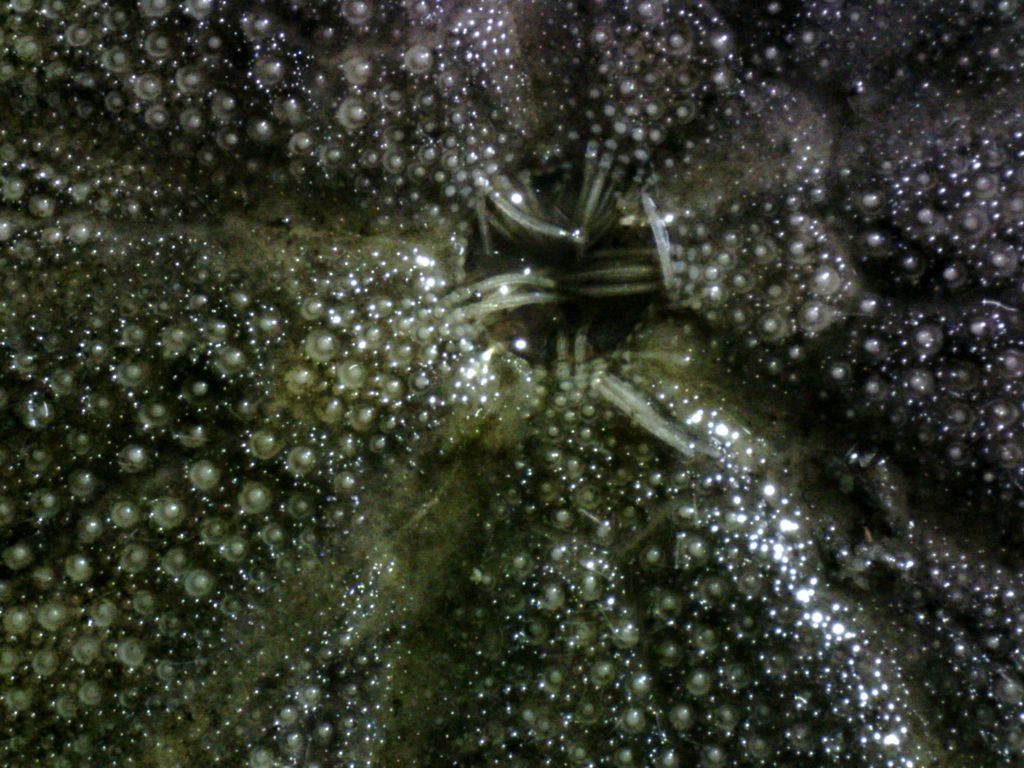

| Live Dendraster excentricus on sand in an aquarium at Shannon Point Marine Center. Found subtidally in Bellingham Bay. Diameter 6 cm. | |

| (Photo by: Dave Cowles, August 2006) | |

How to Distinguish from Similar Species: This is the only species of sand dollar found in Washington and Oregon. As with other sand dollars this species is very flat, at least 5x as wide as tall. All other echinoids in the area are at least half as tall as wide. Several other sand dollars can be found on the Pacific coast. D. vizcainoensis lives in Baja California and has coarser tubercles. D. laevis is smaller and fragile, with a smaller petalidium and lives in deeper water off California. The northern sand dollar, Echinarachnius parma, is flatter, more symmetrical, and the petalidium is more centered on the shell. It lives in Alaska and the Arctic Ocean.

Geographical Range: Alaska to Baja California.

Depth Range: Just below the surf zone on sandy bottoms, down to 40 m depth (but mostly more shallow); some may be found at very low tides on flat sandy beaches.

Habitat: Subtidal on sandy bottoms, on open coast and in sandy lagoons. A few live intertidally and bury themselves.

Biology/Natural History: Adult sand dollars move mainly by waving their spines (movie), while juveniles use their tube feet. The tube feet along the petalidium are larger and are used for respiration. Tube feet elsewhere on the body are smaller and are used for feeding and locomotion. Individuals live subtidally, just beyond the surf, and flat on the bottom or at an angle and partly buried. They frequently move around if they are lying flat. If a current is present they usually lie at an angle and partly buried. Most individuals in the colony will be lying at a similar angle. In very rough water most lie flat and partly buried. Adults feed on detritus and diatoms swept to the mouth by cilia. If lying at an angle, it also catches small prey and algae with its pedicellariae, tube feet, and spines and passes them to the mouth. Their mouth includes a small aristotle's lantern. Predators include the seastar Pisaster brevispinus and the starry flounder Platichthys stellatus. Sometimes settled on by a small barnacle Balanus pacificus. Spawn in late spring and early summer. Fertilization is external. Juveniles swallow heavy sand grains, especially those with iron, which may help serve as a "weight belt" for them. May live 10-13 years. May be aged by counting growth rings on the plates of the test. Relative ages of individuals can be determined by counting the pores in a petal of the petalidium.

Vaughn and Strathmann (2008) discovered that when pluteus larvae of this species are exposed to mucus from a fish predator, they begin to divide asexually by budding and fission. This results in a smaller average size for the larvae and also in a longer time for development. Vaughn and Strathman hypothesized that the adaptive value of this response may be that the smaller individuals are less likely to be eaten by the fish--a refuge in size. Presumably the slower development and longer time they spend as a pelagic larva, which is usually regarded as a disadvantage, is counterbalanced in this case by the temporary avoidance of fish predation.

Steven C. Beadle (1991) notes that dendrasterid sand dollars such as this species are first found in late Miocene sediments in central California. They spread north to Alaska during the Quaternary and supplanted an abundant older fauna of symmetrical sand dollars.

Hardy and Merz (2012) report that juveniles of this species, when inverted, spin around so that the posterior end is facing down-current. That orientation gives them the best configuration for being flipped back upright by the current.

| Return to: | |||

| Main Page | Alphabetic Index | Systematic Index | Glossary |

References:

Dichotomous Keys:Allen, 1976

Flora and Fairbanks, 1966

Kozloff 1987, 1996

Smith and Carlton, 1975

General References:

Brandon

and Rokop, 1985

Brusca

and Brusca, 1978

Carefoot,

1977

Gotshall,

1994

Gotshall

and Laurent, 1979

Harbo,

1999

Hinton,

1987

Johnson

and Snook, 1955

Kozloff,

1993

Lambert

and Austin, 2007

McConnaughey

and McConnaughey, 1986

Morris

et al., 1980

Niesen,

1994

Niesen,

1997

Ricketts

et al., 1985

Sept,

1999

Scientific Articles:

Beadle, Steven C., 1991. The biogeography of origin and radiation: dendrasterid sand dollars in the northeastern Pacific. Paleobiology 17:4 325-339

Chan, Kit Yu Karen, 2012. Biomechanics of larval morphology affect swimming: insights from sand dollars Dendraster excentricus. Integrative and Comparative Biology 52:4 pp. 458-469

Grunbaum, D. and R. R. Strathmann, 2003. Form, performance, and trade-offs in swimming and stability of armed larvae. J. Mar. Res. 61: pp 659-691

Hardy, Adam R. and Rachel A. Merz, 2012. Inverted sand dollars orient themselves in flow to increase likelihood of righting. Invertebrate Biology 132:1 pp 52-61

McEdward, Larry R. and Benjamin G. Miner, 2006. Estimation and interpretation of egg provisioning in marine invertebrates. Integrative and Comparative Biology 46:3 pp 224-232

Strathmann, Richard R. and Daniel Grunbaum, 2006. Good eaters, poor swimmers: compromises in larval form. Integrative and Comparative Biology 46:3 pp 312-322

Telford, Malcolm and Olaf Ellers, 1998. The moving teeth of echinoids. pp. 843-848 in Rich Mooi and Malcolm Telford (eds), Echinoderms: San Francisco. Proceedings of the Ninth International Echinoderm Conference, San Francisco, California USA 5-9 August 1996.

Vaughn,

Dawn and Richard R. Strathmann, 2008. Predators

induce cloning

in echinoderm larvae. Science 319:1503

Web sites:

General Notes and Observations: Locations, abundances, unusual behaviors:

The aboral

side

of the shell (test)

has the off-centered petalidium,

as seen clearly here in a dead specimen which has lost its spines.

Note also that, unlike urchins which have 5, sand dollars have only

4 gonopores, visible around the star-shaped pattern in the center.

The oral (under) side of the

test is flat. It has the mouth in the middle, with

tracks leading

to it.

The anus is near the edge of the shell (at the bottom in this photo).

Although no external ridges are visible around the mouth from the

outside

(see previous photo), this broken piece shows that 5 major and 5 minor

radiating ridges

reinforce the oral side of the test on the inside.

Photo by Dave Cowles, July 2010.

| Close-up oral and aboral views of the small spines on a sand dollar | |

|

|

| Aboral side | Oral side. Photos by Dave Cowles, July 2020, from a specimen from Useless Bay. |

A closeup view of the mouth and the channels that lead to it. Photo by Dave Cowles, July 2020

Authors and Editors of Page:

Dave Cowles (2006): Created original page