Lopholithodes

foraminatus (Stimpson,

1862)

Common name(s): Box crab, Brown box crab, Puget Sound box crab, Oregon

queen crab

|

| Synonyms: |

|

|

Phylum Arthropoda

Subphylum Crustacea

Class Malacostraca

Subclass Eumalacostraca

Superorder Eucarida

Order Decapoda

Suborder Pleocyemata

|

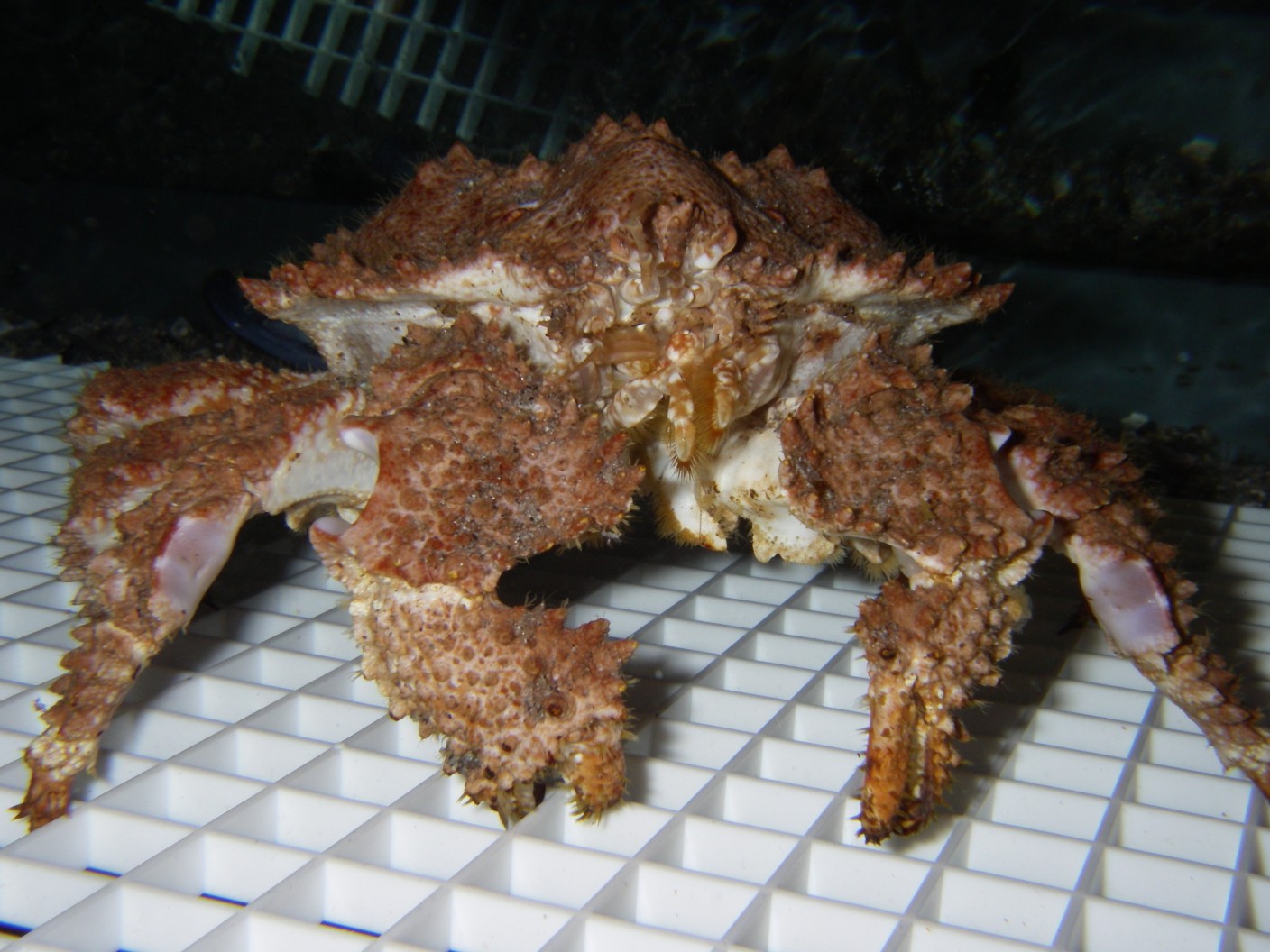

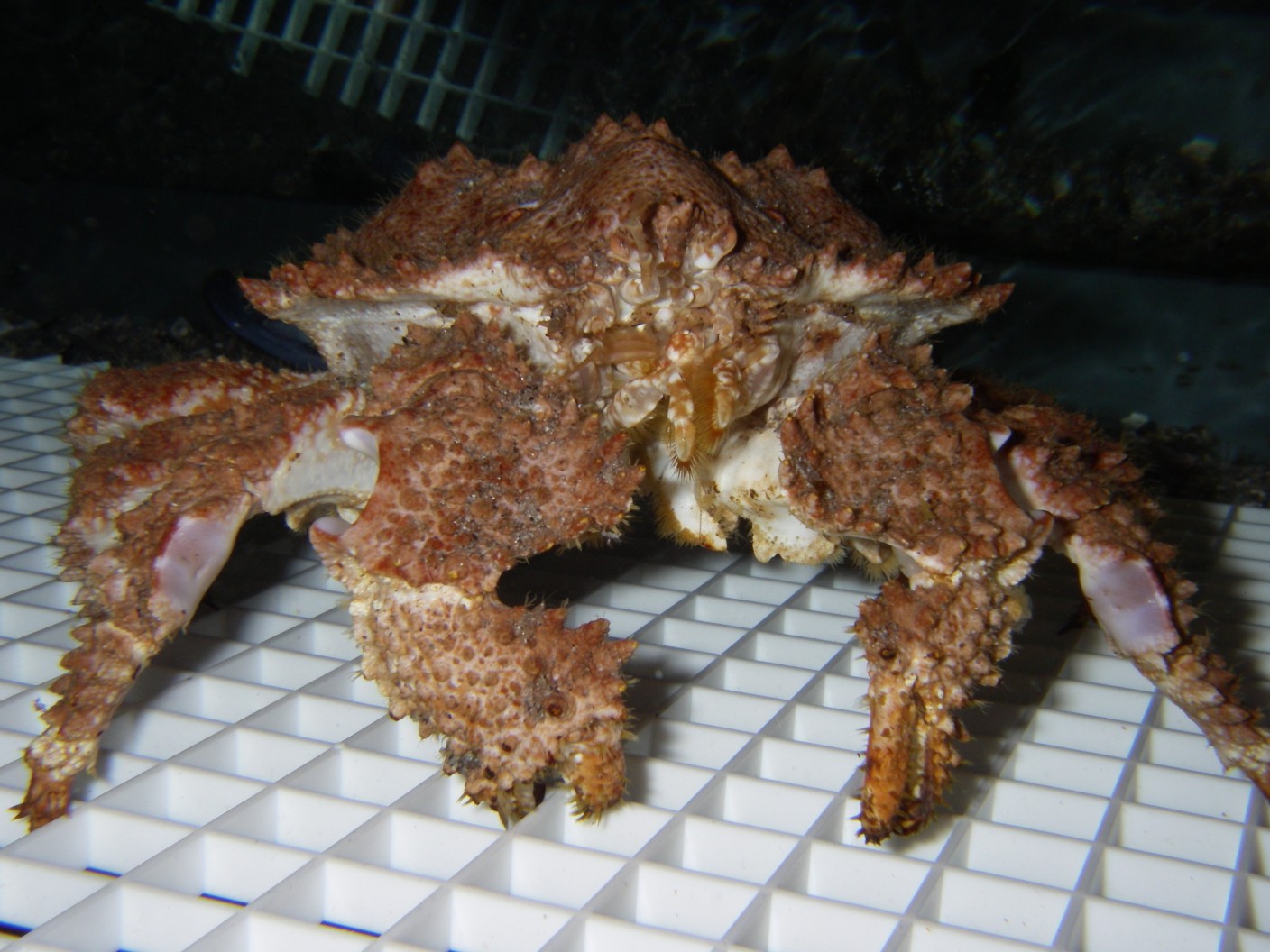

| Lopholithodes

foraminatus

caught by Joe Watson of Campbell River BC at 110-130 m depth in a crab

trap near Twin Island in the Strait of Georgia, Canada. This

is a

large male. The distinctive foramen

created by the legs can be seen to the left, between the base of the chela

and the next leg, lined with smooth purple and white cuticle. |

| (Photo by: Will Duguid,

University of Victoria) |

Description:

The most distinctive

feature of large lithodid crab is the fact that when it pulls its legs

under itself and folds its claws across its front, as it often does, a

large notch on the carpus

of its chelipeds

combined with a smaller notch on the carpus

of leg 2 lie beside each other, creating a prominent tubelike opening

presumably

used for breathing. Other features include the fact that its

abdomen

is completely calcified and its legs are not markedly longer than the carapace.

The carapace

has tubercles

with sharp spines and has no pronounced depression on the

posterodorsal

surface. It is rounded posterolaterally and does not resemble

an

equilateral triangle, and it has no lateral extensions which cover its

legs when viewed from above. The sides of the walking legs

are smooth

and fit together tightly when folded, while the dorsal surfaces have tubercles

and spines (photo).

The merus

of the chelipeds

has lateral extensions on its inner dorsal margin, and the carpus

and propodus

curve upward and cover the mouth when they are folded against the

body.

The largest cheliped

(usually the right) has large, blunt white teeth on the cutting

surface,

while the small chela

has small sharp teeth. The rostrum

is a sharp upturned spine with more spines near the base (photo),

somewhat like that of Rhinolithodes

wosnessenskii. Color is red-brown or

tan with purplish

and white areas. The chelae

are tan and mottled red, with white on the dorsal side and orange or

red

fingers and white tips. Carapace

width to 18.5 cm or larger. Maximum size in males is larger

than

that for females.

How to Distinguish

from Similar Species:

The tubelike passage (foramen) through the folded legs provides certain

identification. Lopholithodes

mandtii looks similar but it is more brightly

colored and has

blunt bumps (tubercles)

rather than bumps with spines on its carapace. Rhinolithodes

wosnessenskii and Phyllolithodes

papillosus have a deep posterodorsal depression

in their carapace. Oedignathus

inermis has a soft abdomen.

Geographical

Range: Kodiak, Alaska

to San Diego, CA

Depth

Range: Low intertidal to 547

m. Usually deep. In the Oregon offshore fishery

they are mostly

caught at 128-165 m depth.

Habitat: Soft

bottoms deeper than

18 m, or on rocky faces overlooking soft bottoms.

Biology/Natural

History: This species

is said to feed by scooping up sediment with its claws, and also to

feed

on the clams it digs up. Will Duguid reports that in the

laboratory

adults of this species are strongly attracted to and feed on brittle

stars.

They may also feed on urchins such as Strongylocentrotus

droebachiensis. It is

thought that octopus may be

its main predator. It may bury itself in the sediment, except

that

the front with the foramen is exposed for breathing. The abdomen

has knobby plates and Flora

and Fairbanks say it is also partly soft and not held very

tightly

against the thorax

(this seems to conflict with other accounts). An intermittent

open

coast fishery for this species exists off Oregon.

This species is said to occur in large aggregations of mixed males

and females on soft bottoms. Molting within an aggregation

seems

to be synchronous, but not synchronized with that of other

aggregations.

Eggs and larvae of snailfish, especially Careproctus

melanurus, the blacktail snailfish, are often found among

the gill

filaments of these crabs. These may occur in large numbers

and even

may contribute to collapse of the gills, but usually they do not seem

to

cause any harm.

Off British Columbia this species has a biennial

(two-year) cycle for

brooding. Females molt and breed during mid-summer, then

brooded

their eggs and larvae for 18 months before releasing them as zoeae

the second winter or early spring (Feb-April) after breeding.

Much

of this long brooding period was due to the fact that the brooded eggs

underwent a 12-month diapause in the gastrula stage. The

females

released the larvae gradually, averaging a period of 69 days.

Brooding

females have a mean carapace

length of 8.9 cm (width 10.7 cm) and a minimum carapace

length of 7.5 cm (width 8.8 cm). Females which have been

brooding

for a number of months and post-breeding females often have extensive

overgrowth

of polychaete tubeworms, hydrozoans, and small bivalves. The

distal

legs and much of the underside has a black stain not seen on males or

pre-incubation

females (Duguid and Page, 2011).

References:

Dichotomous Keys:

Coffin,

1952

Flora

and Fairbanks 1966

Kozloff

1987, 1996

Wicksten,

2009

General

References:

Gotshall and Laurent, 1979

Harbo,

1999

Hart,

1982

Jensen,

1995

Johnson

and Snook, 1955

Scientific Articles:

Duguid, William D.P.

and Louise R. Page, 2011.

Biennial reproduction with embryonic diapause in Lopholithodes

foraminatus

(Anomura: Lithodidae) from British Columbia waters.

Invertebrate

Biology 131:1 pp. 68-82.

Kato, S.,

1992. Box Crab. p. 192 in

W.S. Leet, C.M. Dewees, and C.W. Haugen (eds). California's

living

marine resources and their utilization. Sea Grant Extension,

University

of California, Davis, CA

Parrish, R.H.,

1972. Symbiosis in the blacktail

snailfish, Careproctus melanurus, and the box crab, Lopholithodes

foraminatus.

California Fish and Game 58(8): 239-240

Peden, A.E. and C.A.

Corbett, 1972. Commensalism

between a liparid fish, Careproctus sp. and the lithodid box crab,

Lopholithodes

foraminatus. Canadian Journal of Zoology 51: 555-556

Web sites:

General Notes and

Observations: Locations,

abundances, unusual behaviors:

This species is said to have previously been often found

in the Puget

Sound/Straits of Juan de Fuca region by SCUBA divers at depths below

15-18

m but it is now rarely seen. I have not seen one near the

Rosario

Beach Marine Laboratory but the station museum has a large specimen

captured

years ago. This species is apparently more common below SCUBA depths so

it may by near our station but found deeper than we dive.

This photo of an adult is by Will Duguid

In this closeup of the face the small spinelike rostrum

can be seen. Other features include the spine-tipped tubercles

on the dorsal carapace

and on the dorsal surfaces of the legs and chelae.

Note that in Anomuran crabs the second antennae are based lateral to

the eyes, as can be seen here.

Photo by Will Duguid.

The abdomens

of adult males and females differ in several ways.

This is the abdomen

of a female, which is shown above, is broader than that of a male and

is

asymmetrical.

The plates on the left side of the female abdomen

(to the right above) are larger than those on the left.

The right side of the female abdomen

also has a row of small marginal plates but the left side does not.

The female also has pleopods

on her abdomen,

which cannot be seen without pulling the abdomen away from the thorax.

The abdomen

of a male is not as broad and is more triangular. It has a

small

row of marginal plates on both sides.

The adult male has no pleopods.

Photo by Will Duguid

This photo helps illustrate why these crabs are called box

crabs.

When disturbed they fold their legs and abdomen

together

and hold them tightly against the body so that they are like a tight

box or ball. The crabs on the left side of the seat are

upright while those to the right are upside-down.

Photo by Will Duguid

This front view of a dried specimen shows the distinct openings for

respiratory excurrent flow formed by the front legs when they are

folded

in front of the face. This, no doubt, is the reason for the

'foraminatus'

in the species name. Photo by Dave Cowles, August 2016

This live individual was photographed in the Seaside,

OR aquarium. Photo by Dave Cowles, August 2017

|

|

|

This is the glaucothoe stage. By this

stage the young crab has

a well-developed abdomen with pleopods.

It can swim with the pleopods. |

|

|

|

|

| This crab is an instar III juvenile (3 molts past

the glaucothoe stage).

At this stage it no longer has the pleopods

it had as a glaucothoe, and it walks rather than swims. |

This young crab is an instar VI juvenile (six

molts past the glaucothoe

stage). |

| Lithodid crabs such

as Lopholithodes

foraminatus pass through the nauplius

stage before hatching from the egg. A nauplius

has only 3 appendages, which will become the first and second antennae

and the mandibles

(jaws) in the adult, but during the nauplius

stage they are paddle-like. The crab hatches from the egg as

the

first of four zoea

larva stages (instars). Zoea

larvae swim through the plankton but they do it using some extra

thoracic

appendages which they grew during the molt, called maxillipeds.

After the zoea

stages comes one glaucothoe stage, called a postlarva. The

glaucothoe

swims using pleopod

appendages which have appeared on its abdomen during its

molt. This

is similar to the way a shrimp swims. The glaucothoe molts

through

several juvenile stages which resemble an adult (they walk rather than

swim) but are much smaller. Interestingly, in the molt from

glaucothoe

to juvenile the young crab loses its pleopod

appendages. After several juvenile stages the crab becomes a

sexually

mature adult. In adults of this species the males have no pleopods

but the females re-form pleopods

which are used to carry the eggs. These photos are of

lab-raised

individuals by Will Duguid. |

Authors and Editors of Page:

Dave Cowles (2008): Created original page

CSS coding for page developed by Jonathan Cowles (2007)

|